Migration remains a topic that resonates and stirs strong emotions. Many believe that migrants ‘have it too easy’, or that ‘judges go too far’ when it comes to protecting refugees. But what is the reality? Professor Ellen Desmet, an expert in migration law puts three common misconceptions about migration law into perspective.

In short

- Migration evokes strong emotions but these are often based on misconceptions. Refugees cannot simply come to Europe legally, judges are less activist than claimed and family reunification is far from straightforward.

- By understanding the reality, we can have a fairer debate, one that takes both facts and people into account.

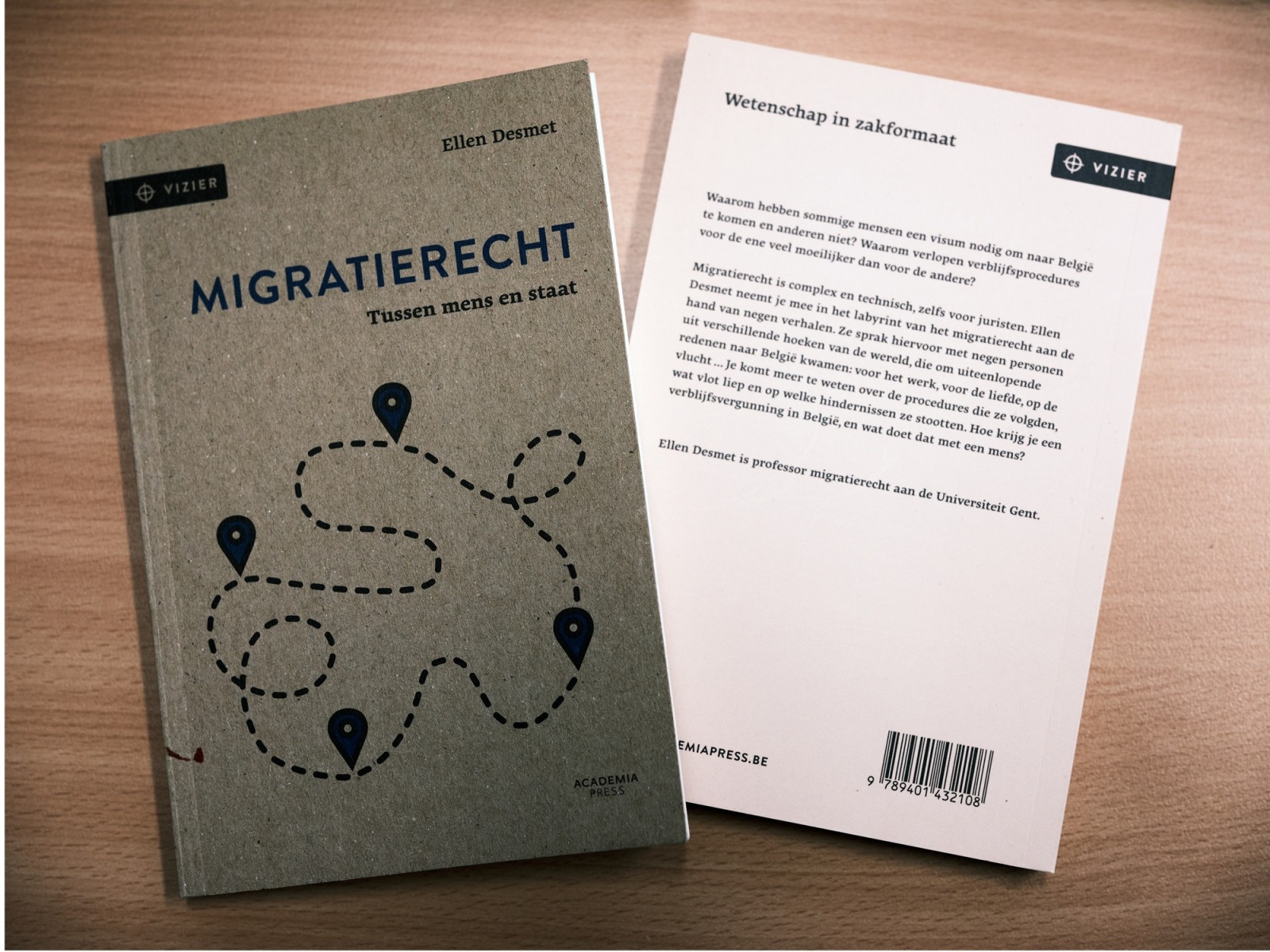

- In her book ‘Migratierecht. Tussen mens en staat’ (in Dutch), Ellen Desmet shows how personal stories and legal facts together shed a different light on the debate. Understanding begins with accurate information and that is exactly what this book aims to provide.

Misconception 1: “Refugees should just come to Europe legally if they want to apply for asylum.”

Why doesn’t someone who is fleeing simply arrive with the correct papers? According to migration law expert Ellen Desmet that is precisely the problem. “It’s an absurd situation. You can only apply for protection once you are physically in Belgium or at the border of a European country, but to get there, you generally need a visa.”

A visa is an official authorisation to enter a country and stay there temporarily. You don’t get one simply by saying you want to apply for asylum. Only tourists, those visiting family or friends, or intending to study or work, can apply for a short-stay visa. You must also be able to prove that you plan to return and that you have sufficient financial means to do so. “For people fleeing war or persecution, coming to Europe legally has become almost impossible. That is why many try to reach Europe on their own, often with the help of smugglers,” Ellen explains.

Another way to enter Belgium legally is through resettlement. “This involves the UN refugee agency selecting vulnerable refugees who have already sought protection in another country, such as Congolese who fled to Rwanda. They are brought to Belgium safely through resettlement to start a new life here. In 2024, this involved 487 people. In March 2025, the Belgian government decided to halt resettlements due to the reception crisis.”

On rare occasions our country also organises rescue operations. “For example, the Belgian government evacuated a number of people from Afghanistan after the Taliban’s takeover.”

According to Professor Desmet, European policy makes it extremely difficult for people to seek protection. Strict border controls, visa requirements and fines for airlines transporting people without the correct papers mean that legal access is almost impossible.

“It’s a catch-22. We shift the responsibility onto the refugees themselves, while we have all but completely cut off the legal avenues for seeking protection here."

Misconception 2: “Judges are (too) activist in migration cases.”

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) is often criticised for ‘going too far’ in its interpretations, for overprotecting the migrants’ rights and for leaving states too little room to control their borders.

This is incorrect, according to Ellen. “That narrative doesn’t align with what scientific research shows: the European Court of Human Rights is actually stricter with migrants than with other groups. A striking example: the Court is more likely to consider it acceptable to detain an asylum seeker than a criminal suspect. This is remarkable, as you would expect people fleeing persecution to receive extra protection.”

This strictness is also evident in other rights, such as the right to family life or the prohibition of inhuman treatment. “The Court sets a high standard for migrants while giving states considerable leeway to shape their migration policies. The political accusation of ‘activism’ is not only incorrect but also misleading.”

However, this doesn’t change the fact that in the past, the Court has issued rulings that provide better protection for migrants. “Think of the ruling on boat refugees in the Mediterranean more than a decade ago, or the case in which Belgium was condemned for returning an Afghan asylum seeker to inhuman conditions in Greece. Those rulings did spark some change,” says Ellen Desmet, “but in recent years the Court has adopted a more cautious attitude.”

Moreover, the European Court is by no means always responsible for migration rules as it oversees general human rights. Laws on reception or asylum are usually issued by the European Union, through negotiation with member states and votes in the European Parliament. “If our executive branch ignores rulings on reception because they hinder policy, it undermines the rule of law,” warns Ellen. “Today, that is dangerous for people fleeing persecution, but tomorrow it could affect detainees and pensioners the day after. It’ a slippery slope.

Misconception 3: “Family reunification is too easy in Belgium.”

A third commonly heard claim is that it’s easy for migrants to bring their family to Belgium. Research shows that family reunification is actually extremely difficult. The rules have become stricter in recent years. Refugees have to surmount huge bureaucratic obstacles when they want to be reunited with their families.

For people with ‘

There is also a small but highly vulnerable group that is particularly affected: unaccompanied minors with subsidiary protection. “They can no longer bring their parents over."

This may seem irrelevant to your own situation but the ever-stricter rules don’t just apply to people fleeing persecution. Belgian citizens who want to bring a foreign partner to Belgium face the same conditions. “For example, someone who meets a partner with a non-European nationality during an Erasmus exchange, must prove that they meet the requirements regarding income and housing. In my book, there is also the story of an Argentinian woman who married here and naturalised as a Belgian citizen. She is no longer allowed to bring her ailing mother to Belgium.”

The strict rules are at odds with what we expect from people fleeing persecution. "We want them to find a job, learn Dutch and integrate quickly but how do you do that if you don’t know whether your children and partner will ever be allowed to come to Belgium? Research shows that this uncertainty causes enormous stress. Family reunification is not a favour, it is a necessary condition for successful integration."

Ellen Desmet is an Associate Professor of Migration Law at Ghent University, where she founded the Migration Law Research Group (MigrLaw). Her book ‘Migratierecht. Tussen mens en staat’ combines legal expertise with personal stories, making migration accessible to a broad audience. She is active within the Human Rights Research Network, CESSMIR and the Human Rights Centre, and received the KVAB Award for Science Communication for her work.

An absolute must-read for anyone reporting on migration.

Migration law is complex and technical, even for lawyers. In her book, Ellen Desmet guides you through the labyrinth of migration law using nine stories. She spoke with nine people from different corners of the world who came to Belgium for various reasons: for work, for love, fleeing from danger…

EOS Publieksfavoriet

Vote for Ellen Desmet for the EOS Publieksfavoriet! On 19 November 2025, she will be recognised for her extraordinary commitment to science communication. Every year, the Royal Flemish Academy and the Young Academy honour researchers who make scientific knowledge accessible to everyone. Ellen Desmet is one of ten laureates selected by the expert jury but your vote can help Ellen win the public award as well.

Read also

Back to university with Davina Simons: "I have many fond memories of my student days"

Als eerste in haar familie die ging studeren, moest Davina Simons (30) het vooral op eigen krachten doen. In 2019 behaalde ze haar master in de rechten aan de UGent. In geen tijd groeide ze uit tot een van de bekendste strafpleiters van het land en vandaag runt ze haar eigen advocatenkantoor.

Human rights: not just for lawyers

Human rights should not only be seen as a legal issue. “They play a role in all disciplines”, says professor of human rights Eva Brems. With a multidisciplinary outlook on the theme, Ghent University is playing a pioneering role. And that is necessary, “because human rights are more than ever under pressure, also in Europe.”

Is environmental protection a human right? The efforts of honorary doctor John H. Knox

More frequent environmental disasters due to global warming, plant and animal species that disappear, ecosystems that are disrupted. These are environmental problems, but increasingly they threaten human rights, such as the right to health or even the right to life. It raises the question: is the right to a healthy environment actually a human right?

Soon no one will be allowed to keep our data (and that's not good news)

The tension between privacy law and criminal law is a ticking time bomb. “We are heading for an unmitigated disaster”, says Professor Gert Vermeulen.