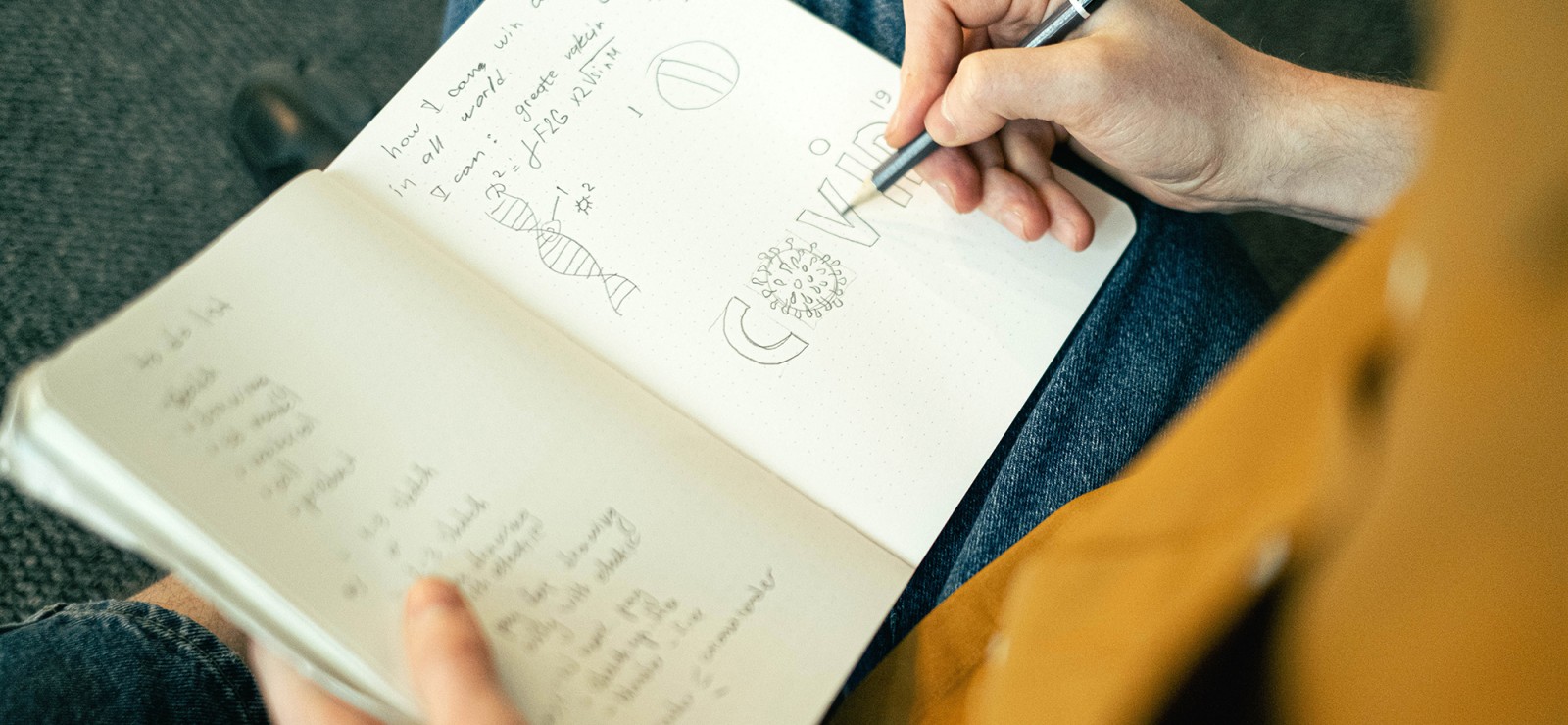

At the moment, it seems that a real boom in conspiracy theories has been unleashed. How is it possible that a completely new virus emerged from nowhere, causing so many deaths? Many believe that it has to be part of a wider conspiracy. The internet continues to be swamped with all sorts of conspiracy theories. Which raises the question: why do so many people believe in the most improbable stories, and why do we have a problem with that?

Are there more conspiracy theories now than before, or does it just seem that way?

Brecht Decoene studied moral philosophy at Ghent University and closely follows numerous social media groups of conspiracy theorists. He does not really see an increase. “I do not have the impression that there are more but it’s actually difficult to determine this objectively and quantitatively."

Depending on the moment, one or the other gets more attention. “In the beginning of the lockdown, I mostly came across conspiracy theories about 5G and corona. Anything about 9/11 or about Hitler fleeing to South America, there was no mention of that for a while. The corona conspiracy theories remained dominant until that terrible explosion in Lebanon. It was reminiscent of the WTC towers, and so everything about 9/11 got a boost again.”

“After that subsided, the corona theories returned. So, conspiracy theories are subject to hypes and trends, to unexpected events.”

The media paradox

The same opinion is voiced by philosopher of science and Ghent University postdoctoral researcher Massimiliano Simons (Sarton Centre Ghent University): “I also don’t believe there are more of them now than before, but they do appear more in the news. Perhaps because conspiracy theories about the coronavirus come across as more threatening. Conspiracy theories that can’t derail important policy or health measures get less attention.”

“That media attention does lead to a paradox. Simply repeating conspiracy theories, even if you want to refute them, gives them a larger audience. Many people only come into contact with them through the media.”

Three typical fallacies

To understand the popularity of conspiracy theories, research has been done on them primarily from a psychological standpoint. What makes conspiracy theories so credible and who are the people who believe in them? Simons: “One notion is that we are all susceptible to conspiracy theories because of certain thinking errors in our brains.”

For example, our brain thinks in two ways: fast and slow. Intuitive on the one hand and rational on the other. “The fast ways of thinking, which often had an evolutionary advantage, lead to thinking errors. Among other things, we tend to attribute an intention to something. For example, in the case of a disaster or an unexpected event - think coronavirus - we look for an intention, such as: the virus was made in a lab.”

Another fallacy is the confirmation bias. “People are more likely to find confirmation of what they already think than to dwell on things that disprove it.” Social medias’ algorithms reinforce this: you follow people or organizations that validate your opinions.

Another typical fallacy is that we want to attribute great cause to great events: the proportionality bias. “There are no or very few conspiracy theories circulating about the failed assassination of Reagan, whereas the assassination of Kennedy is the subject of numerous conspiracy theories still today. But actually, there is no difference between the two events, only the consequences were different. All these fallacies we see surfacing in conspiracy theories about the corona crisis.”

Everyone a conspiracy theorist?

So, everyone is a potential conspiracy theorist. This is also what Brecht Decoene thinks. “A recent survey by Knack states that one in three Belgians believes in a conspiracy theory. The stereotypical image of the socially incapable, paranoid conspiracy thinker is so rare that it is not representative. Most conspiracy thinkers are people like you and me: the neighbor, the bus driver, an engineer with a top job, ... diverse profiles that have one thing in common, a distrust of the establishment.”

“Men and women are equally susceptible, education and age do not play a major role. Even highly educated people go along with conspiracy theories, even though they may think they can spot and reject them right away. Each theory requires a specific technical skill set, while outside our own field we usually know as little as others. Gaps in our knowledge make us more vulnerable to conspiracy stories.”

“Conspiracy theories try to explain why certain things happen,” Massimiliano Simons picks up. “Today’s society is much more dependent on all kinds of experts, whereas in the past you knew everyone in your village and you had to do it all yourself. Now much more is imposed on us from the government, by anonymous experts. The government interfering in our lives on such a large scale is a fairly recent phenomenon. This leads to speculation that is fertile ground for all kinds of conspiracy theories. One element associated with it is the increasing complexity of society. A great deal of contradictory information is presented to us, which leads to uncertainty. Conspiracy theories respond to that uncertainty with a clear answer.”

Our lazy brains

And then there’s laziness as an explanatory factor. “I can understand that laziness,” laughs Decoene. “People are busy: with work, the kids, hobbies, ... A passing message slips by unchallenged. Our brain is also a bit lazy. It uses shortcuts and intuitive thinking. Conspiracy theorists take advantage of this by presenting us with theories that seem logical and confirm our intuitive thinking. But a lot of scientific understanding is counterintuitive, isn’t it? We don’t feel that the earth is spinning at about 900 kilometers per hour; we feel that we are standing still. A lot of scientific insights go against our gut feeling.”

Back to ‘Yes Doctor’?

Massimiliano Simons does not consider conspiracy theories as such to be dangerous. On the contrary, they are even useful to some extent. “Some skepticism is certainly acceptable. A world without conspiracy theories seems to me an unrealistic situation. It may even be dangerous because we will then return to times where authority is not questioned, with all the problems that that entails. Nobody wants to go back to a world where patients are not heard or taken seriously. You can apply that principle to the whole of society. Surely we would prefer to live in a society where citizens can and do ask questions? That means we have to learn to live with a certain amount of skepticism.”

INTERVIEW

Only when skepticism and distrust become the dominant perspective is it a problem. Massimiliano Simons and Brecht Decoene address the question of how we deal with vaccine skeptics.

Massimiliano Simons got his doctoral degree in philosophy at KU Leuven. He is co-founder of the Working Group on Philosophy of Technology (WGPT) and member of the Sarton Centre for History of Science. As a postdoctoral researcher at Ghent University, he mainly conducts research on contemporary technosciences.

Brecht Decoene studied moral sciences at Ghent University. He is a board member of SKEPP (an organization founded by Etienne Vermeersch, among others, which investigates allegations that are highly unlikely according to the current state of science) and author of the booklet “Suspicion between fact and fiction: critically dealing with conspiracy theories” (ASP publishing house, 2016). He has now written a sequel: Twenty Years of Conspiracy Theories.

Opening lecture

Watch Maarten Boudry's free opening lecture on conspiracy theories on Monday 11 October at 19 o'clock: reserve a seat in the Ufo auditorium (Sint-Pietersnieuwstraat 33, Ghent) or follow the livestream on daretothink.be.

Read also

Ghent University virologists combat viruses in new research facility

Every day, professor Xavier Saelens and his team work on new and improved vaccines and medicines to counter flu and corona viruses. Recently, they’ve been doing their work in a new research facility. “Our primary goal: to help those suffering from diseases.”

Done with sticks in the nose? Simple corona breath test coming soon

A corona test that’s as quick and easy as an alcohol breathalyser: it will soon be possible. Researchers at imec-MICT-UGent have been involved in creating a user-friendly device that should be ready for use by the summer.

Is that really your own belief, or is it that of the algorithm?

You may be reading this article because it appeared on your social media timeline. If that is indeed the case, then take a moment to ask yourself whether you have recently been reading other articles on the subject of algorithms. And if the answer to that question is also yes, then the fact that you are reading this shows that the algorithm is working as intended.

Maarten Boudry focusses on conspiracy thinking in opening lecture

Conspiracy theories thrive well on the internet and are not always innocuous. In his second opening lecture as holder of the chair 'Etienne Vermeersch', philosopher of science Maarten Boudry delves more deeply into the pitfalls of conspiracy thinking.