Breast cancer affects one in eight women in Belgium, and is the most common form of cancer in women. Researchers around the world are looking for innovative ways to detect and treat the disease. So are experimental oncologist An Hendrix and medical oncologist Hannelore Denys, two top researchers from Ghent. Can research into extracellular vesicles lead to innovative detection methods and replace (often painful) mammography?

Breast cancer occurs when cells in the breast divide uncontrollably and form a tumour. “Without treatment, these cancer cells continue to grow and can spread to other organs through the bloodstream or lymphatic vessels. Once metastasis has occurred, survival rates drop dramatically, so early detection is extremely important,” explains Hannelore.

Hannelore Denys specialises in the clinical management of breast cancer. As a doctor, she has a lot of contact with patients. As a professor at Ghent University, she also enjoys passing on her knowledge to medical students. Colleague An Hendrix carries out fundamental cancer research. You will usually find An in the lab, looking for new detection and treatment methods long before they are effectively used on patients. The two have known each other for years and work closely together.

Tailor-made for each patient

In addition to early detection, Hannelore stresses the importance of truly understanding the tumour. Each breast tumour is different, so treatment must be different for each patient too. The idea of a single universal cancer treatment is a thing of the past.

“For a long time, surgical removal of the breast tumour and surrounding tissue was the main cancer treatment. Fortunately, this is no longer the case. Surgeries are now much less physically invasive and radiotherapy methods have also greatly improved. Moreover, many new treatment methods have been developed. For example, there have been great advances in chemotherapy with ADC therapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, etc. Indeed, therapies are often combined, depending on the type of breast tumour. A multidisciplinary team will outline a personalised treatment plan for each patient. The result is that ‘one size fits all’ is definitely a thing of the past,” Hannelore continues.

“Since 2010, An has been pioneering research into the diagnostic and therapeutic potential of extracellular vesicles. It’s quite a mouthful, but the results are promising,” says Hannelore proudly. “Together with her colleagues in the Experimental Cancer Research Lab, she is working on something that will greatly advance the detection and treatment of breast cancer.”

Cells communicate with each other via ‘messages’

An enthusiastically clarifies her research. “People communicate with each other all the time. Every day we send out 300 trillion emails around the world. Our cells also communicate with each other via ‘messages’, which we call extracellular vesicles. There are up to a billion of these extracellular vesicles in a millilitre of blood. They are vesicles that are secreted by our cells and taken up by another cell in our body. This is how they influence the behaviour of other cells.”

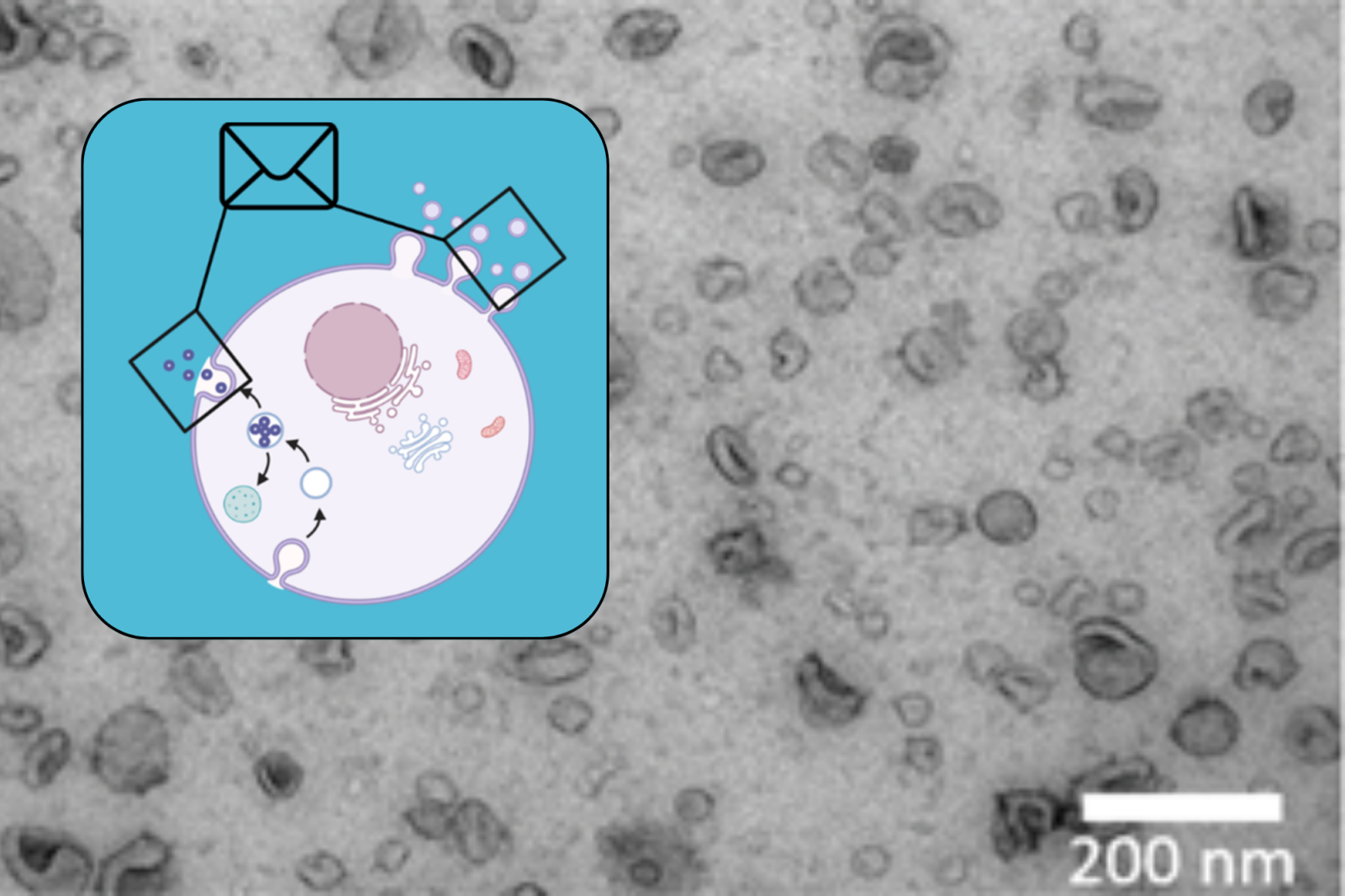

Microscoop image and illustration of cellular vesicles

“If you look at these vesicles with an electron microscope, you immediately notice that they differ enormously in size and shape. What is particularly interesting for oncologists is that the content of these vesicles form an imprint of the cell that secreted the vesicle,” An explains. So the contents of the vesicles tell you more about the tumour? “Exactly! In cancer patients, it gives us more information about the characteristics and activities of the tumour.”

Extracellular vesicles: from waste product to key to early detection

The existence of extracellular vesicles was only discovered in the 1960s. At the time, researchers considered the vesicles to be a waste product of a cell. “During my PhD research, my colleagues and I suspected that this could be the key to the early detection of cancer. Do the vesicles signal the presence of a tumour or cancer? Would these vesicles make it possible to see how breast tumours respond to treatment by simply taking a blood sample? These were attractive hypotheses that we wanted to explore further,” An says.

Thirteen years later, many important steps have already been taken. “First of all, we had to find a way to find these tiny vesicles that come from the breast tumour in the blood and analyse their contents.” The technology to do this did not exist and so had to be developed. “That has been done. We now have everything we need to isolate the vesicles and analyse them piece by piece.”

Bye bye mammography?

Patients can’t use this new detection method yet? “No, our research is still in the experimental phase. It will also be several years before we can start clinical trials. Currently, however, patients are already cooperating by donating blood samples at fixed points in their treatment. We often encourage family members to donate blood samples for the study as well. This cooperation is essential for scientific research. Thanks to this data, we can better understand how the vesicles work and build our clinical model. The better we can map the composition and behaviour of the vesicles, the better we can develop the concrete applications,” An concludes.

Medical progress thanks to research

“We are currently investigating whether we can use the vesicles to monitor whether a certain treatment is succeeding. At a later stage, we would like to intervene in the communication between cells. We think we can disrupt the communication between healthy and cancer cells by manipulating the ‘messages’” explains An.

“We are incredibly grateful for campaigns like ‘Think Pink’ and ‘Fight Cancer’ that raise awareness around the disease. Their financial support makes research possible. Medical progress is only possible thanks to research. And, research never ends. We are always coming up with new research questions,” Hannelore concludes.

Thanks to your donation, you can help researchers achieve even more success. Contact the University Fund and they will provide you with a specific bank reference to support extracellular vesicle research.

Read also

Five (realistic) ways to move more in 2026

January often starts with good intentions… but those plans can be quickly abandoned. To exercise more is always high up everyone’s list, but there’s often a gap between wanting to do it and actually doing it. So how do you bridge that gap?

Is a stool transplant a potential treatment for Parkinson’s?

A recent study into Parkinson’s disease has shown that a stool transplant may constitute a new and valuable treatment of the disease. “It offers a potentially safe, effective and cost-efficient way of alleviating the symptoms and improving the quality of life of millions. A 'bacterial pill' might replace the stool transplant in the future. But more research is needed.”

Ignaas Devisch has been stimulating our thinking for years (and is now receiving recognition for it)

Twenty years ago, he was ridiculed as a scientist when he tried to communicate with the general public. Now, Ignaas Devisch is receiving the Science Communication Career Award for it. "It's wonderful recognition," says the medical philosopher. "Although communicating about science also involves learning to listen well."

‘Women are not just copies of men with breasts and ovaries.’

Van wetenschappelijk onderzoek tot medische behandelingen, decennialang stond de man centraal in de medische wereld. Betekent dat dan ook dat vrouwen daardoor minder goede zorg krijgen?