Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia and ALS are devastating neurodegenerative diseases with no prospect of recovery. Clinical geneticist, physician and Ghent University professor Bart Dermaut is making a breakthrough with his scientific research that could push future therapies in a new direction. This is partly thanks to donations and legacies from patients.

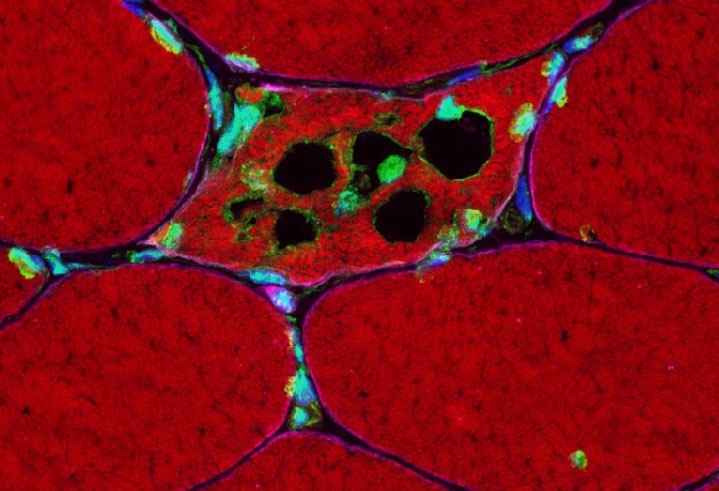

Microscopic image of a dying muscle fibre with TDP-43 clumps (in green).

In 2018, Professor Bart Dermaut’s team began research and genetic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease and related neurodegenerative disorders at Ghent University. A year later, he received a phone call. “A woman had lost one of her close relatives to dementia,” he says. “She wanted to support our research team financially, both through her future estate, and with donations during her lifetime.”

The Alzheimer’s Fund

Her offer surprised and moved Bart Dermaut. “I promised her that I would find out how best to approach that,” he says. He knocked on the door of the Ghent University Fundraising team. “They discussed all the different possibilities with our benefactress. In the end, we decided to set up a fund together: the Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Brain Disorders Fund.”

In the meantime, the Fund has received two additional legacies. “A legacy like that is always unexpected and gives me a great sense of responsibility as a researcher,” says Professor Dermaut. “These legacies help our research move forward. Although I do regret that I could not thank the testators; they are, after all, no longer with us and had never contacted us or the University Fund before. The woman who initiated the Alzheimer’s Fund with is still alive, though. When we set up the fund, we invited her to visit our lab and we are still in regular contact.”

Today, every donation to the Alzheimer’s Fund contributes to a better understanding of Alzheimer’s and related diseases. And you may say so very concretely. For example, a 100 euro donation will be used to detect toxic proteins in cells of dementia patients. With a 500 euro donation, Bart Dermaut’s lab is building a model with fruit flies to study neurological diseases. In fact the fruit fly is perfect for this kind of research, as 75% of genes involved in human diseases have an equivalent in the insect.

Breakthrough in Alzheimer’s research

In recent years, the Alzheimer’s Fund has made it possible for Bart Dermaut’s research team to recruit extra people and carry out many experiments. With results, as there is now a breakthrough.

It has to do with the protein TDP-43. In neurodegenerative diseases, adult nerve cells die in the brain. The prime example is Alzheimer’s disease, which starts with memory problems. It also includes Parkinson’s and the muscle disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). A common feature is that certain proteins begin to clump together in the nerve cells of the brain; in Alzheimer’s disease these are the so-called amyloid plaques and tau tangles. This coming together has a toxic effect, causing nerve cells to die.

“In frontotemporal dementia and ALS, and also in Alzheimer’s disease, protein TDP-43 is one that clumps together most strongly,” says Bart Dermaut. “We have now established that clumping of the ‘top protein’ TDP-43 proceeds differently than previously believed. Fellow scientists have long pondered where exactly the clumping process becomes toxic. Are the clumps themselves toxic or does the run-up to the grouping together cause the toxicity? Our research seems to indicate that it is in the run-up that things go wrong and thus the clumping process becomes toxic sooner rather than later.”

The importance of early detection

Professor Bart Dermaut’s breakthrough underlines the importance of early detection of a neurodegenerative disorder. “The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved three new antibody therapies that remove clumping proteins in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. Clinical studies show a small but demonstrable effect of those drugs. Again, the earlier intervention, the better the outcome.”

The breakthrough is important, but research on TDP-43 is far from complete. “ALS and frontotemporal dementia are completely different disease states despite their relatedness. In families with defects in TDP-43, both ALS and frontotemporal dementia can occur. Until now, it was assumed that in ALS, nerves failed first, followed by muscle deterioration as a result. Our research suggests that the actual problem with TDP-43 is not only in the nerves, but also in the muscles. We now want to explore that further.”

The road to a cure

Diseases like Alzheimer’s or frontotemporal dementia affect a relatively large number of people. Almost 20 per cent of all over 80-year olds are affected by Alzheimer’s. Frontotemporal dementia occurs mostly in people under 60. Early Alzheimer’s is characterised by memory problems. In frontotemporal dementia, the symptoms are behavioural with character changes and speech disorders. As in Alzheimer’s disease, the brain becomes progressively affected over time.

There is no treatment for now, as there are still too many unanswered questions. Questions Bart Dermaut hopes to help answer. All ongoing genetic studies of his research group are based on patients and their families that he also knows as a doctor. “This gives my lab work an extra dimension,” he confirms. “When we have to report the bad news that we have found an inherited defect for Alzheimer’s or another disease, patients always ask: ‘Doctor, is there a treatment? How fast is it progressing now?’ Sometimes those people have witnessed their loved ones deteriorate in a terrible way. They experienced it up close and know what awaits them. The need for therapy is VERY high.”

More needed than research

It makes his task bigger than just research. If a genetic defect is found in someone, other family members also want to be tested. “They have a 50% chance of a bad result; so that’s heads or tails. We handle this very carefully at our centre. Before the test is carried out, there is an initial interview with a geneticist. Then a psychologist gauges motivation for taking the test, as well as being able to deal with it and resilience. Six weeks after the test, the result is available. I conduct these interviews together with the psychologist. Before we communicate the result, we always ask: ‘Do you still want to know?’ Because we respect the ‘right not to know’ at any time.”

It’s a tough task, but he has since found a way to handle those bad-news calls. “Cycling helps. The outdoor air and nature put my mind at rest.”

Want to know more about the Alzheimer’s Fund or are you interested in supporting it yourself?

Read also

Is a stool transplant a potential treatment for Parkinson’s?

A recent study into Parkinson’s disease has shown that a stool transplant may constitute a new and valuable treatment of the disease. “It offers a potentially safe, effective and cost-efficient way of alleviating the symptoms and improving the quality of life of millions. A 'bacterial pill' might replace the stool transplant in the future. But more research is needed.”

‘Women are not just copies of men with breasts and ovaries.’

Van wetenschappelijk onderzoek tot medische behandelingen, decennialang stond de man centraal in de medische wereld. Betekent dat dan ook dat vrouwen daardoor minder goede zorg krijgen?

Kathy (54) fights peritoneal cancer through top-level sport: “Without swimming I lose my anchor”

In March 2021, Kathy received life-changing news: a tumour on her appendix marked the beginning of a long and difficult battle against peritoneal cancer. Yet she decided to do more than fight just for herself. She channels her strength into helping others by raising donations for the Ghent University Peritoneal Cancer Fund.

Deceased Juno’s friends run marathon for cancer research

Friends and relatives of Juno De Hauwere recently gathered at the starting line of the Ghent marathon. They weren’t just looking to achieve a sporting milestone, but above all they were there to honour Juno’s memory and raise funds for leukaemia research.