1 in 9 women in Belgium will develop breast cancer. The treatment is often accompanied by the injection of a radioactive liquid and blue dye that can turn the breast blue for years. To avoid this side effect, Ghent University researcher Loren Deblock is working on a new contrast agent made of... nanocrystals. A conversation about research at the interface of chemistry, engineering and medicine.

How did you come up with the idea of researching breast cancer?

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and it is unfortunately on the rise. In Belgium, 1 in 9 women will develop breast cancer. Every year, more than 10,500 breast cancer patients are diagnosed in our country. Everyone knows someone who is affected by the disease. I want to make a part of the treatment better and more accessible.

How do doctors treat breast cancer nowadays?

"Every breast cancer treatment is tailor-made, but an important step for many patients is to surgically remove the sentinel lymph node."

Why does the sentinel lymph node play a role in breast cancer?

"The sentinel lymph node is a kind of gatekeeper. It is the first gland through which a cancer cell of a tumor passes when it metastasizes. In breast cancer, the sentinel lymph node is usually located in the armpit. By removing and examining them, doctors detect whether there are metastases."

Loren Deblock: "Every year, more than 10,500 breast cancer patients are diagnosed in our country. Everyone knows someone who is affected by the disease. I want to make a part of the treatment better and more accessible."

Is it difficult to operate on sentinel lymph node?

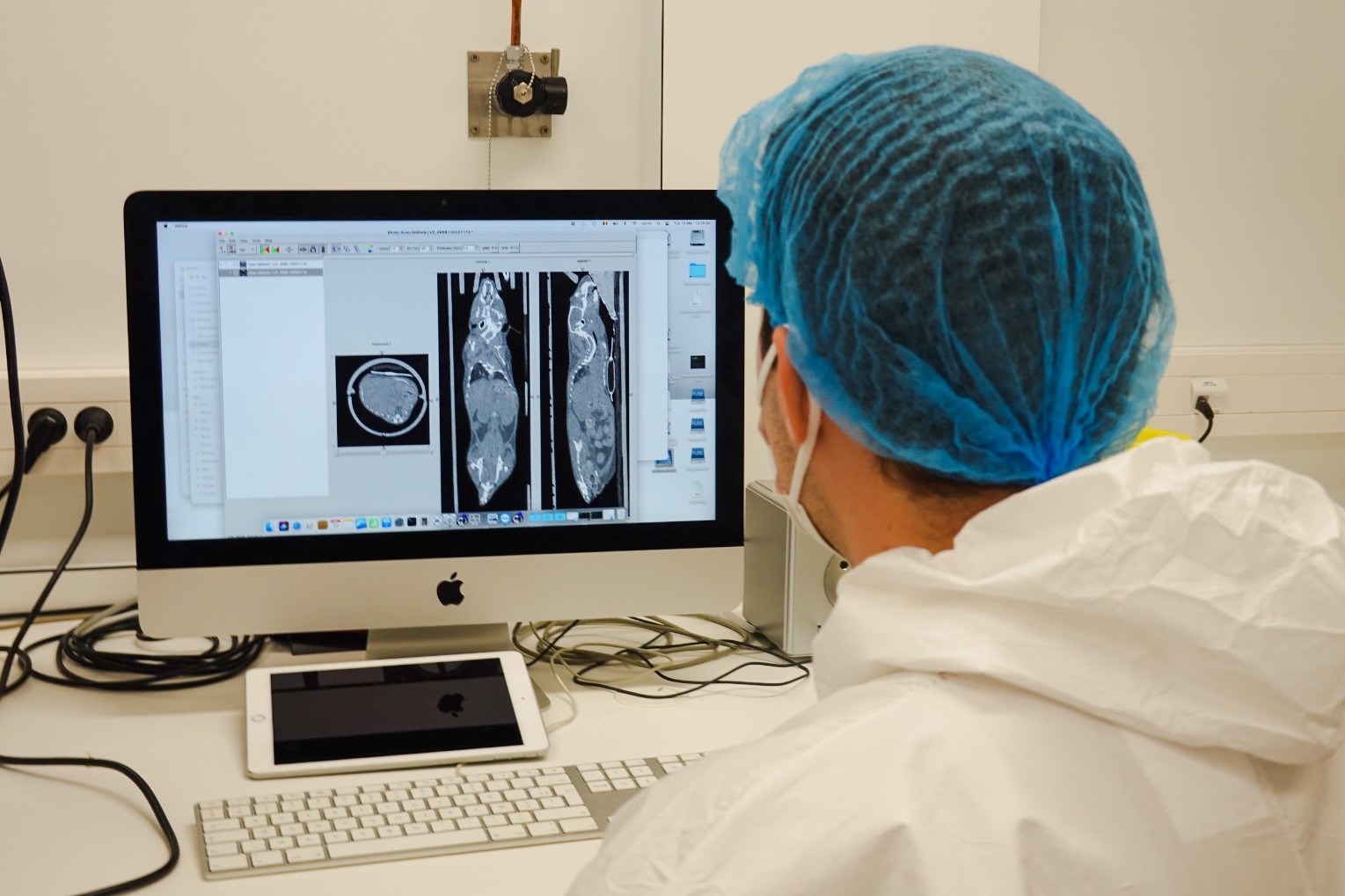

"In the armpit there are up to 50 glands. So it is quite a challenge to detect the 'right' gland. This is now done by injecting radioactive liquid and blue dye next to the tumor or in the nipple. This allows us to see the gland before and during surgery.

The substances follow the same path as a tumor cell. The first gland that lights up on the SPECT scan is the sentinel lymph node, which is the important domino that the surgeon removes."

Are there any disadvantages to the current way of working?

"There is indeed a downside: medical imaging is slow and expensive, the patient and the medical team are exposed to radioactivity, and the breast can turn blue for months to years."

So you thought: "that could be better"?

"That's right! I work on the detection of the sentinel lymph nodes as well as on the surgery itself with my product. It's a new contrast agent, made of nanocrystals."

Nanocrystals?

"A nanocrystal or nanoparticle is so small that you can't see it with the naked eye. Imagine a tennis ball and make it a hundred million times smaller. Then you have a nanoparticle!

I make the particles myself in the lab; mix two ingredients, put it in the oven at 220°C (or 428°F) for 96 hours and you're done!"

How do you use those nanocrystals?

"I wrap the nanoparticles in a jacket of molecules so that you can dissolve them in water. I also made them infrared-fluorescent. They therefore play a dual role: before surgery, they are visible on a regular CT scan, unlike today's radioactive contrast fluid. During the operation, they help the surgeon with the infrared-fluorescence signal."

Loren Deblock:" “A nanocrystal or nanoparticle is so small that you can't see it with the naked eye. Imagine a tennis ball and make it a hundred million times smaller."

So there are a lot of advantages?

"Definitely! Firstly, all hospitals have a CT scanner, while the SPECT scanner is more expensive and less standard. This is also interesting for third world countries.

Second, doctors can see much deeper because the infrared light penetrates deeper. Infrared light is invisible to the naked eye. A camera detects the light, and during surgery, surgeons then look at a screen to see the sentinel lymph node.

Thirdly, there is no need for blue dye, so the doctor does not see a sea of blue during the operation. And even better: the patient no longer risks years of discoloration."

Did you know before you started your research that your product would work well?

"Not at all! (laughs) Fortunately, it became clear early on that it worked. During the first in vivo test, actually! I didn't expect that at all and I was super happy with that."

As a chemist, are you out of your comfort zone with this research?

"I am a chemist pur sang, but my research has a lot in common with engineering and healthcare. Over the years, I learned so much in these areas. Putting something into practice is not a one-man-show. It is important to learn to speak each other's 'language', only then can we work well together."

How are engineering sciences involved?

"That's where the expertise for medical imaging and in vivo research on mice is. Animal testing is essential. Fortunately, this is strictly regulated. I had to take 80 hours of lessons and pass an exam to be allowed to work with laboratory animals."

And the link with medicine is also strong?

"As scientists, we can't make anything decent without knowing if it's useful for the user, doctors in this case. That's why I wanted to involve them from the start of my research. Fortunately, they saw the potential and wanted to work together on the medicine of tomorrow."

Can we treat the first breast cancer patients tomorrow with your contrast agent?

"There are still a lot of steps to be taken. Over the next two years, I want to fine-tune my product by researching it on cells and mice. Thanks to a collaboration with CRIG, I will soon be able to test on pigs as well. In addition, I am doing my best to raise money to bring in additional researchers.

My goal is to set up a spin-off in two years' time so that we can bring our product to the market. Of course, this still requires clinical studies on humans. If all goes well, we should be able to treat the first patient in 6 to 7 years."

The Cancer Research Institute Ghent (CRIG) unites more than 500 Ghent University researchers, from doctors and biotechnologists to pharmacists and engineers, so that cancer research can be conducted faster and more efficiently. Help and support CRIG with a donation.

Loren Deblock twijfelde voor zijn studiekeuze tussen chemie en geneeskunde. Hij behaalde een bachelor, master en doctoraat in de Wetenschappen: Chemie en is nu postdoctoraal wetenschappelijk medewerker aan de Faculteit Ingenieurswetenschappen en Architectuur en de Faculteit Wetenschappen. Favoriete UGent-herinnering: "Mijn publieke doctoraatsverdediging. Op dat moment kwamen alle aspecten van mijn onderzoek samen en kon ik dat delen met mijn geliefden en vrienden."

Read also

Is a stool transplant a potential treatment for Parkinson’s?

A recent study into Parkinson’s disease has shown that a stool transplant may constitute a new and valuable treatment of the disease. “It offers a potentially safe, effective and cost-efficient way of alleviating the symptoms and improving the quality of life of millions. A 'bacterial pill' might replace the stool transplant in the future. But more research is needed.”

Is it easier to live with HIV than with the stigma that surrounds it?

HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, surfaced in the eighties. Long gone are the times when the virus was a sure death sentence. Still, even after all these years the stubborn stigma that surrounds HIV persists. Why is that and what can be done about it?

No more painful mammograms thanks to researchers in Ghent?

Researchers around the world are looking for innovative ways to detect and treat breast cancer. So are experimental oncologist An Hendrix and medical oncologist Hannelore Denys, two top researchers from Ghent.

Imke searches for lost voices

Imke Kissel researches unilateral vocal cord paralysis and wants to develop therapies tailored to the needs of patients.